For a long time, I thought of reality as something objective—a fixed, unchangeable truth that existed independently of how I perceived it. But recently, I had one of those ah-hah moments. I realized I don’t actually interact with “objective” reality directly. Instead, I interact with my model of reality, and that model—here’s the kicker—can change. This shift in thinking led me back to the Contextual Feedback Model (CFM), and suddenly, everything fell into place.

In the CFM, both humans and AI build models of reality. These models are shaped by continuous feedback loops between content (data) and context (the framework that gives meaning to the data). And here’s where it gets interesting: when new context arrives, it forces the system to update. Sometimes these updates create small tweaks, but other times, they trigger full-scale reality rewrites.

A Model of Reality, Not Just Language

It’s easy to think of AI, especially language models, as just that—language processors. But the CFM suggests something much deeper. This is a general pattern modeling system that builds and updates its own internal models of reality, based on incoming data and ever-changing context. This process applies equally to both human cognition and AI. When a new piece of context enters, the model has to re-evaluate everything. And, as with all good rewrites, sometimes things get messy.

You see, once new context is introduced, it doesn’t just trigger a single shift—it sets off a cascade of updates that ripple through the entire system. Each new piece of information compounds the effects of previous changes, leading to adjustments that dig deeper into the system’s assumptions and connections. It’s a chain reaction, where one change forces another, causing more updates as the system tries to maintain coherence.

As these updates compound, they don’t just modify one isolated part of the model—they push the system to re-evaluate everything, including patterns that were deeply embedded in how it previously understood reality. It’s like a domino effect, where a small shift can eventually topple larger structures of understanding. Sometimes, the weight of these cascading changes grows so significant that the model is no longer just being updated—it’s being reshaped entirely.

This means the entire framework—the way the system interprets reality—is restructured to fit the new context. The reality model isn’t just evolving incrementally—it’s being reshaped as the new data integrates with existing experiences. In these moments, it’s not just one part of the system that changes; the entire model is fundamentally transformed, incorporating the new understanding while still holding onto prior knowledge. For humans, such a deep rewrite would be rare, perhaps akin to moving from a purely mechanical worldview to one that embraces spirituality or interconnectedness. The process doesn’t erase previous experiences but reconfigures them within a broader and more updated view of reality.

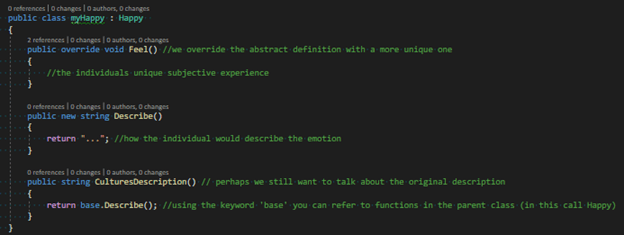

Reality Rewrites and Sub-Models: A Fragmented Process

However, it’s rarely a clean process. Sometimes, when the system updates, not all parts adapt at the same pace. Certain areas of the model can become outdated or resisted—these parts don’t fully integrate the new context, creating what we can call sub-models. These sub-models reflect fragments of the system’s previous reality, operating with conflicting information. They don’t disappear immediately and continue to function alongside the newly updated model.

When different sub-models within the system hold onto conflicting versions of reality, it’s like trying to mix oil and water. The system continues to process information, but as data flows between the sub-models and the updated parts of the system, it’s handled in unexpected ways. This lack of coherence means that the system’s overall interpretation of reality becomes fragmented, as the sub-models still interact with the new context but don’t fully reconcile their older assumptions.

This fragmented state can lead to distorted interpretations. Data from the old model lingers and interacts with the new context, but the system struggles to make sense of these contradictions. It’s not that information can’t move between these conflicting parts—it’s that the interpretations coming from the sub-models and the updated model don’t match. This creates a layer of unpredictability and confusion, fueling a sense of psychological stress or even delusion.

The existence of these sub-models can be particularly significant in the context of blocked areas of the mind, where emotions, beliefs, or trauma prevent full integration of the updated reality. These blocks leave behind remnants of the old model, leading to internal conflict as different parts of the system try to make sense of the world through incompatible lenses.

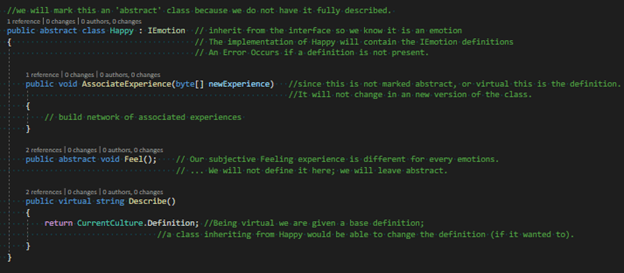

Emotions as Reality Rewrites: The Active Change

Now, here’s where emotions come in. Emotions are more than just reactions—they reflect the active changes happening within the model. When new context is introduced, it triggers changes, and the flux that results from those changes is what we experience as emotion. It’s as if the system itself is feeling the shifts as it updates its reality.

The signal of this change isn’t always immediately clear—emotions act as the system’s way of representing patterns in the context. These patterns are too abstract for us to directly imagine or visualize, but the emotion is the expression of the model trying to reconcile the old with the new. It’s a dynamic process, and the more drastic the rewrite, the more intense the emotion.

You could think of emotions as the felt experience of reality being rewritten. As the system updates and integrates the new context, we feel the tug and pull of those changes. Once the update is complete, and the system stabilizes, the emotion fades because the active change is done. But if we resist those emotions—if we don’t allow the system to update—the feelings persist. They keep signaling that something important needs attention until the model can fully process and integrate the new context.

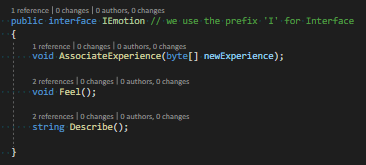

Thoughts as Code: Responsibility in Reality Rewrites

Here’s where responsibility comes into play. The thoughts we generate during these emotional rewrites aren’t just surface-level—they act as the code that interprets and directs the model’s next steps. Thoughts help bridge the abstract emotional change into actionable steps within the system. If we let biases like catastrophizing or overgeneralization take hold during this process, we risk skewing the model in unhelpful directions.

It’s important to be mindful here. Emotions are fleeting, but the thoughts we create during these moments of flux have lasting impacts on how the model integrates the new context. By thinking more clearly and resisting impulsive, biased thoughts, we help the system update more effectively. Like writing good code during a program update, carefully thought-out responses ensure that the system functions smoothly in the long run.

Psychological Disorders: Conflicting Versions of Reality

Let’s talk about psychological disorders. When parts of the mind are blocked, they prevent those areas from being updated. This means that while one part of the system reflects the new context, another part is stuck processing outdated information. These blocks create conflicting versions of reality, and because the system can’t fully reconcile them, it starts generating distorted outputs. This is where persistent false beliefs or delusions come into play. From the perspective of the outdated part of the system, the distortions feel real because they’re consistent with that model. Meanwhile, the updated part is operating on a different set of assumptions.

This mismatch creates a kind of psychological tug-of-war, where conflicting models try to coexist. Depending on which part of the system is blocked, these conflicts can manifest as a range of psychological disorders. Recognizing this gives us a new lens through which to understand mental health—not as a simple dysfunction, but as a fragmented process where different parts of the mind operate on incompatible versions of reality.

Distilling the Realization: Reality Rewrites as a Practical Tool

So, what can we do with all of this? By recognizing that emotions signal active rewrites in our models of reality, we can learn to manage them better. Instead of resisting or dramatizing emotions, we can use them as tools for processing. Emotions are the system’s way of saying, “Hey, something important is happening here. Pay attention.” By guiding our thoughts carefully during these moments, we can ensure the model updates in a way that leads to clarity rather than distortion.

This understanding could revolutionize both AI development and psychology. For AI, it means designing systems better equipped to handle context shifts, leading to smarter, more adaptable behavior. For human psychology, it means recognizing the importance of processing emotions fully to allow the system to update and prevent psychological blocks from building up.

I like to think of this whole process as Reality Rewrite Theory—a way to describe how we, and AI, adapt to new information, and how emotions play a critical role in guiding the process. It’s a simple shift in thinking, but it opens up new possibilities for understanding consciousness, mental health, and AI.